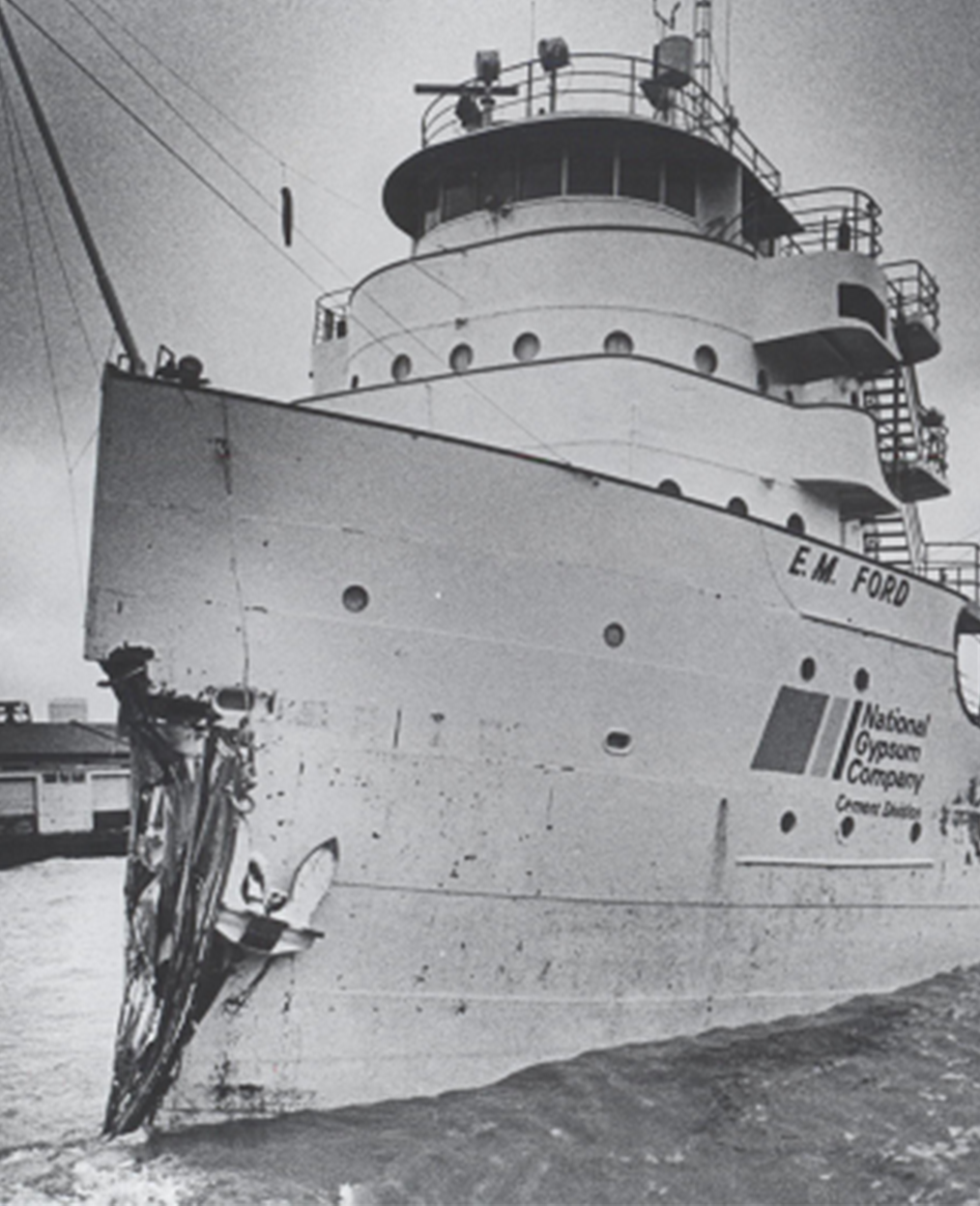

E.M. Ford Carrier

On Christmas Eve (12/24) in 1979, the cement carrier E.M. FORD was ripped from her moorings in slip one of Milwaukee’s outer harbor and battered against dock walls during a storm. With a hole punched in her bow and loaded with 7,000 tons of cement, she slowly sank in the slip. After raising the vessel, crews moved her to the inner harbor and began chiseling out hardened cement. E.M. FORD was back at work before summer ended. The legal mess, however, would take more than eighteen years to resolve.

The E.M. FORD began her career as the PRESQUE ISLE. Launched in 1898 by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company at Lorain, Ohio, she was 428 feet long with a 50-foot beam. She operated mainly in the ore and coal trades for Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company.

To compete with newer vessels, the FORD’s hull was rebuilt in 1915 at the Great Lakes Engineering Works. Her new hull incorporated arched construction, which eliminated vertical hold stanchions. This increased cargo capacity and made unloading much easier.

By 1955 ore carriers had grown significantly larger and the PRESQUE ISLE was sold to the Huron Portland Cement Company of Alpena, Michigan. During the winter of 1955-56, she was converted to a bulk cement carrier at the Christy Corporation in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. The rebuilt vessel was christened E.M. FORD in honor of Huron’s chairman, Emory Moran Ford.

In April of 1956, as she began her career as a cement carrier, the FORD’s steering gear failed. She collided with and sank the A.M. BYERS in the St. Clair River. The FORD stayed afloat but suffered extensive bow damage. She received a new bow at the Great Lakes Engineering Works and returned to the Lakes.

After her maiden season, the FORD headed back to the Christy shipyard where her forward superstructure was replaced by a three-level pilothouse that featured comfortable guest quarters. Her aft cabins would be rebuilt at Fraser shipyard in 1960.

On December 19, 1979, the FORD departed Alpena, Michigan, with 7,000 tons of dry cement. She arrived Milwaukee on December 21 and docked at a berth in slip one of Milwaukee’s outer harbor. She was to wait there for a fleetmate before moving to the Huron Cement terminal on the Burnham Canal.

At a meeting on December 22, FORD’s captain informed the assistant dock superintendent that the boat would be laying up for the holiday and most of her crew would be gone until December 26 or 27. The superintendent warned that slip one could “get a little rough” if a storm came up. Nevertheless, most of the men, including the captain, left for the Christmas holiday. Only five remained on board.

To secure the vessel while the crew was gone, sixteen lines were put out. These were a mix of 4½-inch nylon ropes and one-inch steel cables.

Unfortunately, no one was assigned to watch the weather. And none of the crew on board could access the vessel’s telephone. In an emergency, they were to use a nearby pay phone.

A powerful storm hit Milwaukee Christmas Eve. Straining against gale-force winds and 13-foot waves, the FORD’s mooring lines began giving way. About one that afternoon, the crew radioed the Coast Guard for help. Tugs came out but were unable to assist.

No longer secured, the FORD was repeatedly driven into the dock walls. A large hole was punched in her bow and cracks were visible along her port side. All five men aboard were safely evacuated and the boat settled on the bottom of the slip Christmas Day.

The FORD was raised January 20, 1980, and moved to the inner harbor. It took several weeks to chip away hardened cement and make temporary repairs so she could be towed to Sturgeon Bay. She entered the graving dock at Bay Shipbuilding on March 6. After extensive repairs, she was back at work in August.

Meanwhile, the FORD’s owner, National Gypsum Company, and 32 insurers sued the City of Milwaukee seeking $6.5 million – the cost of raising and repairing the vessel. Thus began an 18-year odyssey through the federal court system. The case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court and is memorialized by at least five published opinions. Although the city was only 1/3 at fault, it ultimately paid more than $9 million.

The late Harney B. Stover, Jr., a member of the Wisconsin Marine Historical Society, represented the ship’s owners and underwriters. He wrote about the case for Soundings (Winter 1999 and Spring 2000). These and other issues of Soundings (Newsletter) have been digitized and are available on our website at: wmhs.org.

In 1984 and 1985, the FORD sat idle. During that period she was used for storage at Milwaukee. After receiving a temporary permit from the Coast Guard, she sailed under her own power to Sturgeon Bay in May of 1986. She passed her five-year inspection and returned to active duty.

When the modern cement barge INTEGRITY entered service in 1996, the FORD was towed to Saginaw, Michigan, where she served as a storage hull. After 110 years on the Lakes, she was sold for scrap in 2008.

NOTES:

McAllister Brothers, a New York City ship salvage company, was brought in to raise the FORD. Edward E. Gillen, a Milwaukee marine contractor, assisted in the effort.

About thirty persons were ticketed for illegally parking on the Hoan Bridge to view the sunken cement carrier. The fine: $37.

After this incident, Milwaukee had a notice placed in the United States Coast Pilot, a manual used by mariners in unfamiliar ports, warning of “severe surging” in the city’s outer harbor when there are strong northeast winds.

HAVE A VERY MERRY CHRISTMAS!

PHOTO CREDITS: Unless otherwise noted, Great Lakes Marine Collection of the Milwaukee Public Library and Wisconsin Marine Historical Society.

https://www.vos.noaa.gov/MWL/apr_06/shipwreck.shtml

https://www.vos.noaa.gov/MWL/apr_06/shipwreck.shtml

https://www.vos.noaa.gov/MWL/apr_06/shipwreck.shtml

My Uncle Larry was one of the first people on the boat once they got the pumps going he was working getting the boilers going so they could get the ship up and running. Timing was critical. I was on the boat with my dad delivery Gordon-Piatt parts while part of the ship was still submerged.

~Dan McCotter